The big question should be why is Elon Musk so happy to chat with Jokowi?

By now we have already plenty of information on how Indonesia (and also Thailand) is leading Malaysia by a large margin when it comes to automotive policy and also the electric vehicle ‘race’.

To start, we have had a staggered national automotive policy (NAP) due to the years of corrupt practices from our Malaysian Automotive Institute (MAI) who decided to rebrand themselves a few years ago to MAAri in order to widen their corruption game. Fueled by corrupt automotive media (two in particular) who gave them plenty of publicity they staggered the Malaysian automotive landscape to suit their personal agenda.

Today, MAAri is under investigation and their corrupt media partners are silent. This is Malaysia at its best.

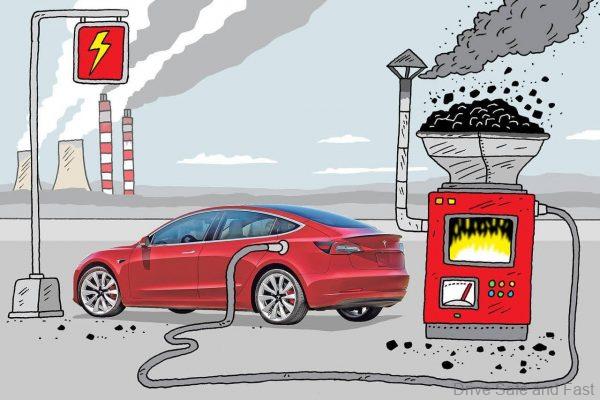

Now, when it comes to Elon Musk, the big drama is all about Tesla electric vehicles and the opening of a car manufacturing plant, battery manufacturing plant and also the EV charging infrastructure which brings not only plenty of jobs, but also the rest of the electric vehicle business links.

So, why is Elon Musk ready to work with Indonesia and not Malaysia right now? Well, it is clear and precise government policy that gives confidence to Elon Musk to start operations.

Indonesian President Joko Widodo back in August 8, 2019, signed a regulation on the promotion of battery-powered road vehicles (PP No. 55/2019), a move that was welcomed by industry associations and gave car manufacturers a clear understanding of the Indonesian EV roadmap. This Malaysia and MAAri did not provide.

Indonesia’s government set a goal for EVs to make up 20 per cent of all domestic cars manufactured, equal to around 400,000 e-cars, by 2025. With motorbikes favoured over cars nationally, the government also aims to have e-motorbikes make up 20 per cent of the total domestic motorbikes production.

According to the Ministry of Industry, there are 15 domestic e-motorbike manufacturers with a production capacity of up to 877,000 e-motorbikes annually. Malaysia is not anywhere near this figure right now.

To sweeten the deal with all foreign car manufacturers, the Indonesian Ministry of Industry, set a goal to provide 1 million cars for export to the ASEAN region by 2025, of which twenty percent will be electric vehicles. We already see Hyundai doing this with the IONIQ 5.

New export markets would probably have to be tapped for this. So far, cars made in Indonesia are mainly exported to less developed countries in Asia, the Pacific, the Middle East and Central and South America, which have low purchasing power and are still lacking in infrastructure for battery-powered vehicles. Europe, North America and China are currently not among the target markets.

Among other things, the current Presidential Decree creates the legal basis for battery production, local content requirements, charging stations and possible tax incentives. For example, by 2021, electric cars produced in Indonesia must have at least 35 percent local content, at least 40 percent by 2023, at least 60 percent by 2029, and at least 80 percent by 2030. How exactly these seemingly high-priced shares are measured is not described, though these may be specified in subsequent regulations.

In addition, the Presidential Decree allows electric vehicles to be partially dismantled (IKD – Incompletely Knocked Down) or partially (CKD – Completely Knocked Down) – as long as the domestic industry cannot produce the required components. Moreover, until local companies are able to ramp up their own production, complete electric vehicles (CBU – Completely Built-Up) may be temporarily imported.

Electric charging stations should be easily accessible according to the regulation and they should have their own parking spaces. They are to be created primarily at petrol stations, shopping malls, rest areas, government buildings and apartment complexes. The development of a charging infrastructure should be fiscally promoted.

The production of electric vehicles should be supported by tax and non-tax incentives. The tax incentives include the reduction of import duties on components or the promotion of exports and the promotion of research and development. A non-fiscal measure could be about the exemption of electric vehicles from certain driving restrictions, such as the odd-even license plate policy currently implemented in Jakarta.

Next is a simple numbers game. Indonesia has a large vehicle market compared with other ASEAN countries. Its two-wheeler market is twice as large as that of the next largest in the region and it was the 2nd largest passenger vehicle market in the ASEAN region in 2020.

In 2019, total domestic sales of passenger cars, buses, and trucks published by the Association of Indonesia Automotive Industry (GAIKINDO) were 1,030,126 units and total domestic sales of two-wheelers as published by the Association of Indonesia Motorcycle Industry (AISI), were 6,487,460 units. Malaysia is just a fraction and it is not growing as our currency and economy takes a beating.